Key Points

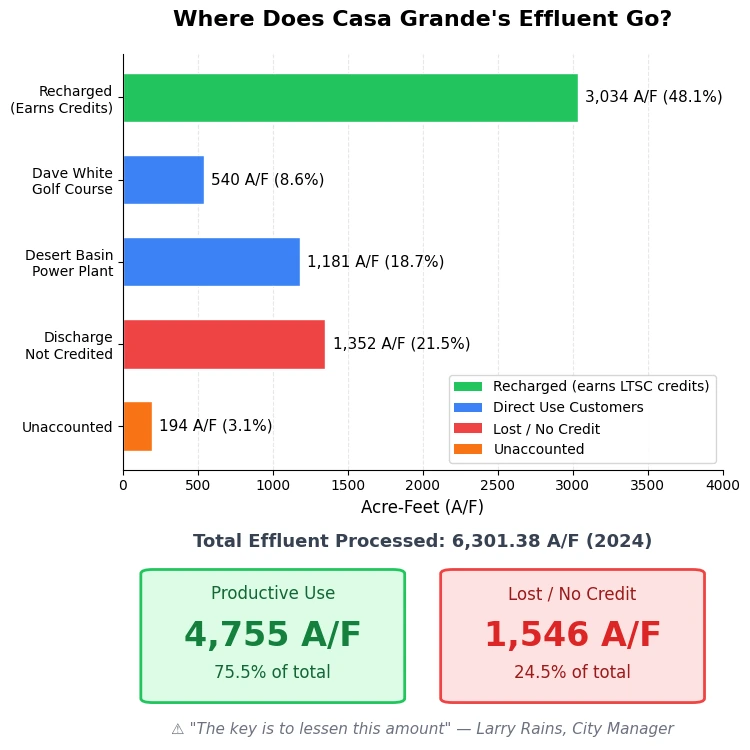

- Casa Grande processed 6,301 acre-feet of treated wastewater in 2024, but nearly 25% received no credit due to upstream flows, physical losses, and accounting factors

- The city earns credits for only half of effluent stored at its wash-based recharge facility. A facility built specifically for recharge—rather than using a natural wash—would earn full credit for the water that reaches the aquifer.

- Two industrial users have requested a combined 2,000 acre-feet of effluent for direct use

- Arizona’s new Alternative Designation of Assured Water Supply (ADAWS) program makes effluent a “key” resource for meeting 100-year water supply requirements

- City expects to finalize an effluent allocation strategy by end of February 2026

Casa Grande City Council held a study session December 15 to discuss how the city manages its treated wastewater and plans to allocate this resource as development pressure grows. City Manager Larry Rains presented a Casa Grande effluent allocation strategy overview, explaining current uses and challenges the city faces in maximizing this resource.

This was the first in a planned series of four or five study sessions on water and effluent topics, scheduled to continue through January and February 2026.

What Happens to Casa Grande’s Treated Effluent

City Manager Larry Rains described treated effluent—also called reclaimed water, recycled water, or treated wastewater—as “a valuable resource” due to its “reliability, cost-effectiveness, and its ability to extend groundwater supplies.”

Casa Grande’s Water Reclamation Facility treats wastewater to A+ quality standards, which Rains described as “the highest quality standard for reclaimed water in Arizona.” The facility is nearing completion of an expansion to 18 million gallons per day capacity, according to his presentation.

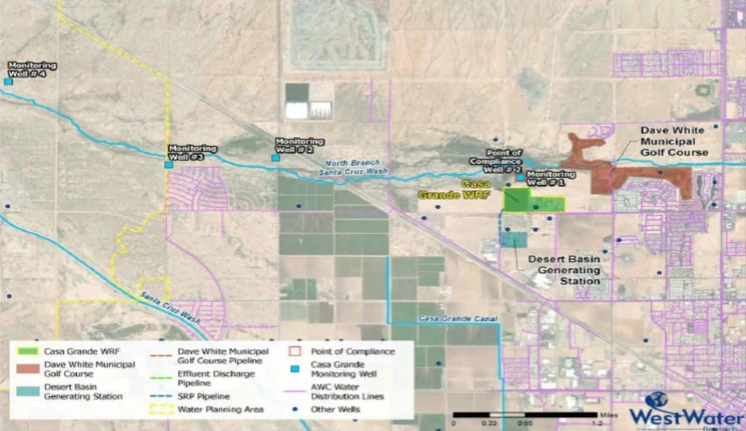

According to Rains, the city’s treated effluent currently goes to three places. Dave White Municipal Golf Course receives direct deliveries for turf irrigation. Desert Basin Generating Station receives effluent for industrial cooling processes, blending it with Central Arizona Project water. The remaining effluent flows into the North Branch of the Santa Cruz Wash. This natural stream channel serves as a managed recharge facility, allowing water to percolate into the underlying aquifer.

Rains noted that treated effluent “supports direct and indirect potable reuse,” but added that typical uses are “turf irrigation and industrial processes.” Potable reuse refers to treating wastewater for drinking water purposes and requires additional permitting. Direct potable reuse means treated wastewater goes straight into the drinking water system. Indirect potable reuse means treated wastewater first passes through an environmental buffer—such as an aquifer or reservoir—before being withdrawn for drinking water. Turf irrigation and industrial cooling are non-potable uses, meaning the water will not be consumed.

He mentioned that five years ago, the city built a reuse line on Bianco Road “specifically for industrial reuse,” making effluent available for industrial development. “Typically, what you find is that they’re going to use it for their cooling towers,” he said.

Why Effluent Management Matters

Rains explained why tracking and maximizing effluent use has become critical for Casa Grande’s future.

When effluent is recharged into the aquifer and not recovered by the end of the calendar year, the city can earn Long-Term Storage Credits, according to Rains. These credits can be used to establish an Assured Water Supply or fulfill replenishment obligations. They can also be sold or transferred to developers.

“At some point, I do envision these being monetized and then sold perhaps for development,” Rains said.

Councilmember Matt Herman distinguished between “direct users who are actually using the water” and “paper water” that “attributes to use down the road, the long-term storage credits.” Rains confirmed this distinction.

The credits have become more important due to recent state policy changes. Arizona established a new Alternative Designation of Assured Water Supply (ADAWS) program in November 2024, and the first designation was issued to water provider EPCOR in October 2025. Rains called treated effluent “key” to the new program because “it is a flexible renewable water resource” that can be credited toward the 100-year assured water supply requirement. He said the city plans to invite Arizona Water Company to present details about the alternative designation at an early 2026 meeting.

According to the presentation, Casa Grande held 8,764 acre-feet of storage credits as of 2021. The North Branch of the Santa Cruz Wash recharge facility was permitted in 2013 but did not become fully operational until 2017. Credit accrual has grown since then:

- 2017: 162 acre-feet

- 2018: 1,658 acre-feet

- 2019: 2,331 acre-feet

- 2020 and 2021 combined: 4,613 acre-feet

Rains noted the Arizona Department of Water Resources “does indicate they’re behind in calculating” and awarding credits, which is why data beyond 2021 is not available.

However, recovering these credits requires wells within the “area of hydrologic impact,” according to Rains. He described this as the geographic boundary within which recharging effluent into the aquifer has caused groundwater levels to rise at least one foot. Wells must generally be within one mile of the recharge facility.

“While we’re generating these credits, there are still additional infrastructure that’s necessary to be able to draw that recovered effluent from the aquifer,” Rains said. He suggested the city may need to recharge effluent in other locations to create additional recovery areas.

System Losses: Nearly 25% of Effluent Without Credit

A significant portion of the presentation focused on inefficiencies in the current system. According to figures Rains presented, Casa Grande processed 6,301 acre-feet of effluent in 2024. The city’s wash-based recharge facility has a permitted volume of 3,500 acre-feet for recharge purposes. As shown in the image below, about 75% went to productive use while nearly 25% was lost or received no credit.

“We had 1,351 acre-feet of effluent that did not get recharged or reused,” Rains said, referring to discharged water that received no credit. An additional 194 acre-feet was unaccounted for. “In my mind, as we rebuild our strategy and we look to allocate our effluent, the key is to lessen this amount,” he said

Councilmember Matt Herman asked for clarification: “So, to be clear on that. We actually put the water out but we don’t get credit for it, right?”

Rains confirmed this, calling it “a lost supply” because no credit is awarded. He explained the water still enters the aquifer but the city receives no storage credits for it.

The losses occur because of how managed recharge facilities work, according to Rains. When stormwater, irrigation district discharges, or other upstream flows enter the wash, the city does not generate storage credits during those periods. He explained that neighboring irrigation districts use the wash as a discharge point. The state water department also accounts for losses from vegetation, evaporation, and other factors when calculating credits, according to Rains.

Additionally, state rules impose a “cut to the aquifer”—a percentage of stored water retained by the aquifer rather than credited to the storer. For effluent stored at wash-based facilities like Casa Grande’s, this cut is 50%, meaning only half of the water that reaches the aquifer is credited. A facility built specifically for recharge—rather than using a natural wash—would receive a 0% cut for effluent, earning full credit.

“Ideally, you would want to have another recharge facility available to capture that or you would want to have a direct use customer that could ultimately acquire that,” Rains said. He suggested the city may need to build recharge facilities in other locations—not in a natural wash—to avoid competing flows. Options could include recharge basins, which allow water to percolate into the ground, or injection wells, which pump water directly into the aquifer.

Herman emphasized the point: “Especially the 1,352 we’re not getting credit for.”

Current Effluent Agreements and Commitments

Rains outlined existing agreements for treated effluent:

Dave White Municipal Golf Course receives between 520 and 550 acre-feet annually for turf irrigation. Rains called it “our longest customer” of several decades.

Desert Basin Generating Station has a 40-year agreement dating to 2001 for approximately 1,568 acre-feet annually (about 1.4 million gallons per day), according to Rains. The power plant uses the effluent in its steam generators and turbines. The agreement includes options for four additional five-year renewal terms.

Copper Mountain Ranch, a master-planned community in northern Casa Grande, has an agreement originally signed in 1999 and amended in 2007. Rains said he “suspects that as that development moves forward, there’ll be some dialogue” and “likely some changes.”

City of Casa Grande Water Company received an allocation of 1,370 acre-feet of storage credits in 2021. The council approved this allocation toward the city’s Designation of Assured Water Supply “for the purpose of increasing the volume of assured water supply within the boundaries of the designation,” according to the presentation. Rains noted elsewhere that the city-owned water company is intended to serve development, primarily Copper Mountain Ranch.

Industrial Requests for 2,000 Acre-Feet

According to Rains, two industrial users have formally requested a combined total of approximately 2,000 acre-feet of effluent for direct use. These companies want to build infrastructure to connect directly to the city’s effluent system.

Herman asked whether these companies would need to obtain water one way or another. Rains confirmed they currently use groundwater from Arizona Water Company or would need to build new infrastructure to pump groundwater if they don’t receive effluent.

Other Water Policy Changes Mentioned

Rains also briefly mentioned two other recent policy changes:

Ag-to-Urban Legislation allows property owners using land for agriculture to convert that water allocation to development purposes, according to Rains. Under the program, eligible holders of irrigation grandfathered rights can retire groundwater pumping and generate credits that can be used toward assured water supply requirements. Rains said he anticipates providing more details in future sessions.

Water Availability Fee Tariff was recently filed by Arizona Water Company with the Arizona Corporation Commission. Rains said it “requires individual developers to bring new water to Casa Grande for development.” More specifically, the tariff is designed to recover from developers the cost of securing additional long-term water supplies needed to meet assured water supply requirements for new subdivisions.

Additionally, Rains said the city continues working with the state water department on an amended Designation of Assured Water Supply for the city-owned water company outside city limits. This application has been in process for approximately three years.

Developing the Strategy

Rains said the city will evaluate allocation approaches—including whether to set percentages for residential versus industrial users, and whether to prioritize direct reuse or storage credit generation.

“The goal is to establish a strategy that best serves the needs of existing and future users while limiting the processed volumes that are not reused or recharged,” Rains said.

External consultants are assisting and Rains hopes to be “pretty well wrapped up by the end of February.” Additional study sessions are scheduled for January and February 2026.